Impacts of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris Mill.) on long-term hydrology at the watershed scale

Abstract

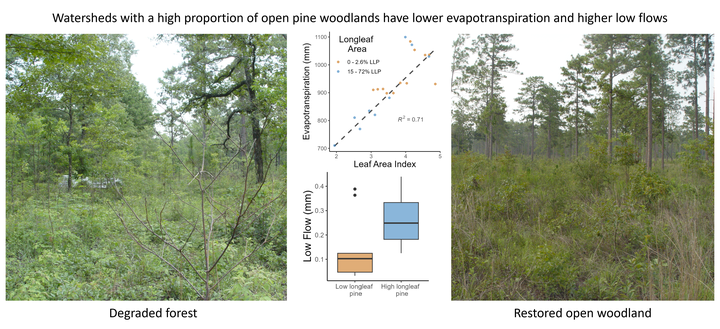

Threats from climate change and growing populations require innovative solutions for restoring streamflow in many regions. In the arid western U.S., attempts to increase streamflow (Q) through forest management have had mixed results, but these approaches may be more successful in the eastern U.S. where greater precipitation (P) and lower evapotranspiration (ET) offer greater potential to increase Q by reducing ET. Longleaf pine (Pinus palustris Mill.) (LLP) woodlands, once the dominant land cover in the southeastern United States, often have lower ET than other forest types but it is unclear how longleaf pine cover impacts watershed-scale hydrology. To address this question, we analyzed 21 gaged rural watersheds. We estimated annual water balance ET (ETwb) as the difference between precipitation (P) and streamflow (Q) between 1989 and 2021 and quantified low flow rates (7Q10) among watersheds with high and low LLP cover. To control for climate variability among watersheds, we compared variation in hydrology metrics with biotic and abiotic variables using the Budyko equation (ETBudyko) to understand the differences between the two ET estimates (∆ET). Watersheds with 15–72 % LLP cover had 17 % greater mean annual Q, 7 % lower annual ETwb, and 92 % greater 7Q10 low flow rates than watersheds with <3 % LLP. LLP cover decreased ET and increased Q by 2.4 mm or 0.15 % Q/P per 1 % of watershed area, but only when LLP was managed as open woodlands. Our results demonstrate that ecological forest restoration in these systems, which entails mechanical thinning and re-introduction of low-intensity prescribed fire to maintain open woodlands, and enhance understory diversity, can contribute to decreases in ET and increases in Q in eastern forests.